Let me speak of my crimes!

l wail, I cannot hold back my sobs.

In the bedroom there is weeping.

In lament and wailing I suffer every day.

Lord, bitterly I raise a cry to you, hear me!Ashurbanipal, speaking a ritual lament in Babylon 648 BCE

Thus spoke Ashurbanipal, King of the Assyrians, grieving for the destruction of Babylon (in what is now modern Iraq) one of the most magnificent cities of the ancient world. The jarring note in this lament however is that Ashurbanipal himself was responsible for the destruction.

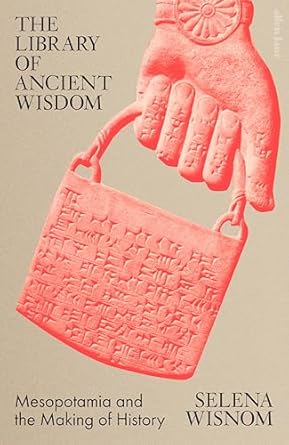

Selena Wisnom describes the scene in her new book The Library of Ancient Wisdom: Mesopotamia and the Making of History: 'The palace is a smoking ruin, and the streets are choked with corpses, scavenger animals grow fat on the flesh of the starved dead.'

Ashurbanipal - who presided over the empire at its territorial peak - has just concluded a bitter war against his brother Shamash-shum-ukin who had been appointed king of Babylon by their father as a way of preventing a fratricidal scramble for the throne when he died. The arrangement held out for twenty years but then exploded into a full scale war. It has taken Ashurbanipal four years of hard fighting to defeat the 'rebels', kill his brother, and reduce Babylon to a charred ruin.

Why then at the height of his triumph is he so contrite?

Think like an Assyrian

Wisnom's book is an attempt to explain the Assyrian perspective on the world to the modern reader. And just as the modern reader might head to the local library to understand the modern world, remarkably we can also take a look around Ashurbanipal's library to understand the world of the Assyrians in 650 BCE.

The reason we can do this is because their 'library books' were clay tablets. These clay tablets become virtually indestructible when baked hard1. Because the Assyrians were overthrown and their major cities burnt down not long after Ashurbanipal's reign, this fire effectively preserved his tablets forever. Bad news for the Assyrians, but good news for us.

Assyrian decimal classification

If we categorise his ancient library books we can reverse engineer the Assyrian Dewey Decimal Classification system, which Wisnom broadly presents to us as chapters in her book:2

- 000 Magic and Witchcraft

- 100 The Treatment of Disease

- 200 Extispicy, or entrail divination

- 300 Astrology

- 400 Literature

- 500 Lamentation

Perhaps the key takeaway is that almost all sections in the library relate one way or another to human relations with the gods and the supernatural. This is because for the Mesopotamians in general (as well as most humans throughout history) the gods and world they lived in were so interconnected that they were one and the same thing. In a way then there is no supernatural, it is all just natural.

If you want to understand the world you must understand the gods, and if you understand the gods you will understand the world, now and in the future. As Wisnom3 puts it:

Belief was not a choice; the gods were just a part of the world that everyone took for granted. It would be like asking whether we believed in the sun.

Selena Wisnom, The Library of Ancient Wisnom

Lamentable

The Lamentation section of the library was particularly interesting to me as it feels like the most remote from our own libraries. In this section you can find famous laments from the past: defeated people bewailing the sack and destruction of their cities. But you can also - and to us this is quite strange - find tablets for the daily laments that professional lamentation priests would chant in temples - even though everything was actually absolutely fine.

Here is one that was recited daily in a temple in perfect working order, but imagining it's destruction:

Its crenelated wall has been destroyed. Its dove hovers about.

Its doorframe has been torn down. What was once a place of marvel is no more.

Its rafters lie exposed to the sun like a man felled by disease.

It's jutting brickwork and scratching in tears like a mother in mourning.

Its reed mat is contorted like a person suffering from colic.

Its reed eaves are lying in the ground like plucked hairs.

Like a flying bat its... has disappeared into the ruin mound.Come out like the sun! (A lamentation)

So if everything is fine and the temple has not fallen down what are they lamenting? Wisnom speculates that the reason so much assiduous attention was given to these chants was that 'The gods would hear these songs and would be pleased that the people recognised their almighty power, and thus would not feel the need to demonstrate it. It is a clever piece of reverse psychology.'

Crocodile tears

Going back to Ashurbanipal's lament after his destruction of Babylon with which I started this review: it appears that this highly ritualised lamentation is the metaphysical equivalent of clearing away the rubble and starting afresh.

By describing the destruction in impersonal terms Ashurbanipal implies that it is the work of the gods (acting through him and his soldiers), which is now complete, and that the city can now be restored. By extension it wasn't really all due to him going on a psychotic, vengeful bender against his own sibling.

In reality I got the feeling that the only thing Ashurbanipal really regretted was not having the pleasure of murdering his brother himself.

I'll just have a quick look at my tablet

The whole 'scheduled lamenting' thing is quite different to what we are used to nowadays, but other areas of the library are more familiar. For example a physician could consult tablets that might help him figure out what was wrong with his patient, just as a doctor would use google today4.

And while a doctor might now recommend downloading a mindfulness app to help reduce the causes of some illnesses, a physician then could work in tandem with an exorcist who would recommend rituals to block any evil magic or placate a slighted deity which may well have been the underlying source of the misfortune.

Overall I was impressed by the intricate, interconnected and highly specialised knowledge that a Mesopotamian scholar would accumulate to understand how their world fitted together.

Bad behaviour

Of course the thing that the Assyrians are best known for is their extreme brutality: the kings loved to boast of their prowess in smiting, beheading, flaying and mutilating their enemies. Perhaps the most famous examples of this are the palace relief wall carvings, now in the British Museum, showing Ashurbanipal's troops slaughtering Elamites, and Ashurbanipal himself relaxing in his garden with a severed head hanging in a tree close by.

Lest we get too judgemental Wisnom reminds us that the 20th century was probably an even more appalling bloodbath, the only difference is that our leaders don't choose to decorate their living rooms with scenes of them smiting their defeated foes.5 While I am not myself an Assyrian apologist, I do agree with Wisnom that there is much more to understand about them than just their bloodthirstiness.

Style guide

I found The Library of Ancient Wisdom nicely structured and easy to read. As well as the library texts themselves we are introduced to some of the people who wrote them: each chapter starts off with a short imagined scene - for example Balasi the king's chief Astrologer scrutinising the night sky for the planet Mercury, or Dannaya the liver reader preparing his sacrifice - which I thought worked really well as a way to draw us into this world.

What I liked most

What I really appreciated about the book is that it made the Assyrian outlook on the world make sense.

When you hear occasional snippets about the Assyrians, such as they cut open livers to discern the will of the gods, it all sounds a bit bonkers.

But presented as a systematic whole, as Wisnom does in her book, it turns into something actually pretty reasonable. For example, the liver when fresh is the same colour as clay, Wisnom tells us. And it often has little marks on it that look very similar to cuneiform wedges. If you think the gods have their hands in literally everything then it makes sense that the Assyrians would look to interpret these marks as signs from the gods.

Conclusion

Getting into the entrails of this book was a hugely pleasurable experience for me. And by poring over the text carefully I can confidently predict strong sales and many satisfied readers.

Hence all the old pot fragments you can admire in museums around the world. ↩︎

She also has chapters on the scribal art, the power of the gods, war and a day in the life of Ashurbanipal, but these don't relate directly to the books in the library. ↩︎

I also like the Terry Pratchett quote that 'it is like asking whether you believe in the postman'. ↩︎

Or perhaps Chat GP? ↩︎

This is not quite correct - I went on a tour of the Houses of Parliament in the UK recently and there are plenty of massive paintings celebrating British victories over the French, although there were no severed heads to be seen. ↩︎

Book details

(back to top)- Title -

The Library of Ancient Wisdom : Mesopotamia and the Making of History

- Author -

Selena Wisnom

- Publication date -

February 2025

- Publisher -

Allen Lane

- Pages -

448

- ISBN 13 -

9780241519639

- Podcast episode -

The Book Club: Selena Wisnom Mesopotamia and the Making of History

- Amazon UK -

- Amazon US -