What are the origins of the modern European state?

It’s not a question I have given a great deal of thought to up to now, but the author’s very useful explanation of prevailing theories in this field makes clear that it is a question that has consumed academic careers.

In this book, Anna Grzymala-Busse has done something that I think is a characteristic of good non-fiction writing: she’s made me think afresh about contemporary concepts and institutions that I had largely taken for granted: ideas such as a ‘fictive’ person, separate legal personality, representation, consent, majority and supermajority decision making, all originated somewhere.

Explaining where those ideas came from and how they spread forms the subject matter of this book.

War and negotiation

According to the author there are, at present, two dominant theories regarding the origins of the modern European state: the so-called ‘bellicist’ theory and the ‘bargaining’ theory.

The ‘bellicist’ tradition is best summed up by its principal proponent, Charles Tilly, who said in 1975 that ‘war made the state and the state made war’1. In the early modern period2, European political entities consolidated and centralised to make themselves more effective at fighting wars, which gave rise to the state. References to ‘states’ before this period are, in this theory, anachronistic.

The bargaining tradition likewise locates the origins of the European state in the early modern period but argues that state institutions arose from a process of ‘bargaining’ between society and rulers. Society granted rulers steady income streams and, in exchange, rulers granted ‘society’ protection in the form of property rights. The Glorious Revolution (1688) is Exhibit A in this theory.

What did the medieval Church ever do for us?

But Anna Grzymala-Busse raises an interesting flaw in the above periodisation: most of the characteristics of European states, such as taxes, government institutions, and systems of law, pre-date early modern Europe; most arose in medieval Europe.

It appears that she is not the first to look back further to understand the European state, with recent work considering the impact of the Crusades, and the rise of cities and communes, among other factors. But, in most of these accounts, the role of the Church is essentially seen as a blocker – a conservative force seeking to slow down or reverse attempts to ‘modernise’ political organisation. The author turns this theory on its head: instead, she sees the medieval Church as instrumental in the development of the European state, essentially by the dual forces of imitation and competition.

This, she claims, explains why the European state developed in a way so distinct from other regions of the world. One of the defining features of Europe in this period is the existence of an independent trans-national institution which claimed spiritual authority (and often precedence) over secular regimes.

Nullify vs nuture

That does not mean that the Church was intending to foster the growth of secular institutions and legal systems – far from it; quite often those were the unintended consequences of intense competition between the Church and medieval secular power (principally, the Holy Roman Empire).

Where the Church felt itself most threatened by a secular power, in what is now modern Germany, it was effective at fragmenting alternative sources of political authority whilst engaging in intense internal reform and innovation to strengthen itself in its power struggles with the emperors.

Meanwhile, elsewhere, where the Church felt less immediately threatened (most notably England) secular powers learnt from and adapted the institutional and legal innovations of the Church to their own purposes.

The greater and better part

The book has a wealth of insights and new information I was not previously aware of. As someone who works in the legal profession, I was interested by the way legal concepts from ancient Roman law (often private law) were ‘rediscovered’ by medieval canon lawyers (often studying in the newly formed universities in places such as Bologna) and then repackaged for use in the Roman Catholic Church’s institutions and for methods of decision making.

Something as simple as majority decision making, which seems entirely intuitive to us today, was an institutional innovation by the Church based on the Roman law concept of maior et senior (the greater and better part) which, over time, came to be interpreted as the more numerous part (i.e., the majority). Before that, the assumption had been that decisions should be taken by consensus (usually meaning unanimity).

Ideas such as this were then spread by clergy who had either worked in parts of the Church and/or studied in the new universities, but who also formed a large part of medieval secular bureaucracies and decision-making forums.

How a political scientist does history

The book has a very distinctive style, which took me a while to get used to, but which I ultimately found quite refreshing. The reason for this may be (although I’m speculating) that the author is not writing as a historian, but rather as a political scientist. If you look her up, she comes up under the Stanford Department for Political Science and is described as a Professor of International Studies.

I’m used to reading history books by persons who would probably principally identify themselves as historians. How does this impact on the style of the book? The first thing I noticed is the complete absence of what might be described as the ‘anecdotal’ style of history writing.

To give a sense of what an anecdotal style history book is like, see my review of Blazing World by Jonathan Healey who, as I mention in my review of that book, loves anecdotes. I think most historians do. They set a scene, and can give a non-fiction book a more narrative, story-like, feel.

No tittering at the back

Ms Grzymala-Busse very much has her own style, and that style involves no amusing or eye-catching anecdotes. Quite a few Popes and Holy Roman Emperors make appearances, and occasional monarchs elsewhere. But other than that, individuals and their deeds are largely absent from this book. What we are given instead are lots of maps, diagrams and at times quite heavy-going statistical analysis of evidence, which I admit I frequently did not follow fully.

At one point, we are told that ‘figure 4.3 reports the results of mixed-effects random intercept regressions on city-level data with city and year clusters’. There is an appendix on ‘data and robustness tests’ (which I skipped) and the book is littered with references to ‘regression analysis’, ‘dependent variables’ and suchlike things which washed over me. But it all sounded clever and convincing, so I’ll take it on trust that Ms Grzymala-Busse knows what she is talking about.

But if the above gives the impression that the book is, overall, onerous to read, that would be unfair. One of the things I enjoyed was its straightforward and clear writing style.

Whilst I did not always follow the workings of the statistical analysis, in each case, that analysis resulted in a clearly stated conclusion (for example, that increasing warfare in early modern Europe corresponded with the fragmentation of states rather than their formations); those ideas, in turn, feed into an overall thesis which is succinctly set out in the introduction and conclusion of the book.

Approaches to history

It reminded me of a module I did in my first year of history at university called ‘approaches to history’ where we read history from a cross-disciplinary perspective (in my case I chose sociology and anthropology). This is history as done by a political scientist and is a useful corrective to the perhaps lazy stylistic habits which historians can fall into. Personally, all the number crunching didn’t detract from my enjoyment of the book, but then again it is only 183 pages long, which may have helped.

Conclusion

This is a book which raises interesting questions about what makes European political institutions and legal systems distinctive and where that distinctiveness came from. It also makes a strong case. It turns out the medieval Catholic Church did rather a lot for us, even if they weren’t always intending to.

Book details

(back to top)- Title -

Sacred Foundations : The Religious and Medieval Roots of the European State

- Author -

Anna M Grzymała-Busse

- Publication date -

January 2023

- Publisher -

Princeton University Press

- Pages -

256

- ISBN 13 -

978-0691245072

- Podcast episode -

- Amazon UK -

- Amazon US -

Next post

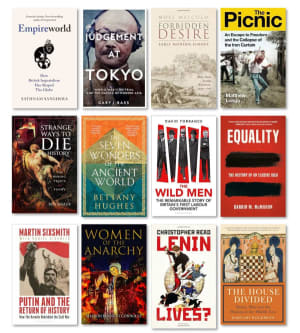

← New history books in January 2024

Last post

A history of the universe - mapping the past →