Nowadays we suffer from deforestation. In the 13th Century England had an afforestation problem. More and more of the country was being forested and people were - literally - up in arms about it. What was going on?

Dan Jones fills us in, in: In the Reign of King John: A Year in the Life of Plantagenet England.

When we hear about forests we might conjure up mighty oaks or soaring pines. But back in 1215, the year of the Magna Carta, forests were instead associated with the abuse of power. Calling somewhere a forest was equivalent to King John saying “mine!” - a forest meant land exclusively reserved for the King.

Arboritrary justice

The expansion of the Forest under John, and his immediate predecessors also had the effect of putting “men at the mercy of a much more stringent and expensive code of law with no means of protest.” Typical punishments for offences such as killing animals in the forest, or simply gathering firewood were heavy fines or - if you couldn’t pay the fine - mutilation.

Forest land was not necessarily woodland: it could be agricultural land or moorland as well. By the end of the 12th Century forest lands covered from a quarter to a third of the country1. John loved his forests because (a) he liked hunting forest animals but also and more importantly (b) it was a really important source of cash. If you wanted to graze your animals on forest land for example you had to pay for the privilege.

Pay per chew

So if the land you relied on to support yourself and your family was suddenly turned into forest land you could be in big trouble - you couldn’t take wood, you couldn’t kill animals and you couldn’t graze your flock - without paying extra.

Then and now

It must have been a bit like the radical re-zoning of the streets near where I live in London, in the year 2016. We had previously been able to freely park our cars on the streets outside our houses, but due to an arbitrary decision of Merton council, we were suddenly required to pay annually for this privilege. Perhaps the main change since Medieval times was that those who complained didn’t get their ears cut off.

What's the problem?

Back to the past - this wasn’t the only grievance against King John:

- he had been demanding eye-wateringly huge sums of money from his barons on the flimsiest of pretexts,

- he had lost in war almost all of the land that he had inherited in France including, embarrassingly, Normandy where many of the English barons would have presumably owned estates

- he had capriciously hounded to death anyone who got up his nose

- he had built fish traps all over the place2

In the winter of 1215 the situation had become critical with leading barons determined to do something about this turbulent king. After mediation with the king had failed they took the radical step of declaring war on him which quickly turned into a stalemate: the barons held London which contained the Treasury and other important bits of government. The King held a whole load of impregnable castles all over England.

This was the context in which the Magna Carta was signed - as a peace treaty between the two sides - and the story which Dan Jones tells us in his book.

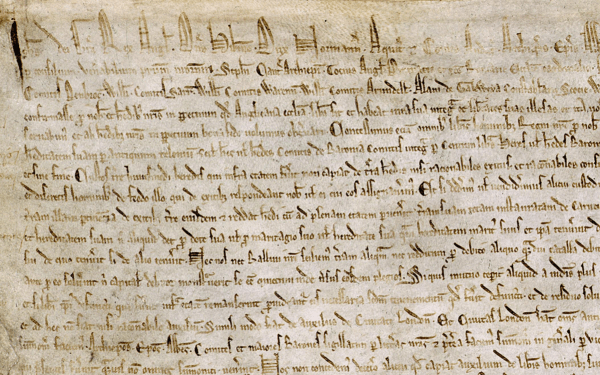

One of the four surviving copies of the 1215 Magna Carta, this one from the British Library. Image credit: Magna Carta article on Wikipedia

The structure of the book

Jones’ book has two separate strands. The first strand is a narrative history of the year 1215 where Jones briskly and entertainingly whisks us through the events of the year, starting with John celebrating Christmas at the end of 1214 with feasting, singing and no doubt carousing - and ending the year with John embroiled in a civil war as he tried to renege on his Magna Carta agreements, celebrating the yuletide period by planning a campaign of destruction and devastation across his own kingdom.

Everyday life

The second strand is an attempt to paint a picture of what life was like for more ordinary people at that time. So after hearing about John’s 1214 Christmas for example we get a section on what clothes people wore: generally speaking whatever they could afford. As Jones nicely puts it:

for peasants, too, clothing was a marker of status, and in a sense a badge advertising their political capital and potency, which is to say that in general they had none.

Dan Jones, In the Reign of King John

We also get sections on eating and drinking, health, the law, language and names, women and children, and animals.

At the end of the book we are provided with the full text (translated) of the 1215 Magna Carta and the 1217 Charter of the Forest.

What I liked

The great thing about this book is that it is so short and accessible. If you just read the narrative bits covering what happened in 1215 and skip the social history bits - more on this later - you will get through it in no time. But still with the feeling that you are fully immersed in that time and place.

And if you have the vague impression that the Magna Carta is a bit boring this book will go a long way towards changing your mind!

Keeping it real

It does this by delving into the context behind the Magna Carta. So a clause on royal forests goes from being incomprehensible and obscure to the urgent question of whether or not your nose gets chopped off. Abuse of the royal prerogative becomes a story of turning against your friend and starving his wife and son to death in a dungeon.

Which then helps us think about that old question of what makes John a “bad king”? Didn’t all English kings behave in a similar way? Was it just that you could get away with it if you won your battles? Or was John a different kind of bad? Jones gives us enough of the detail for us to draw our own conclusions.

Finally the book is filled with some very beautiful illustrations - mostly high quality snippets from illustrated manuscripts showing scenes from everyday life.

What didn’t I like?

I feel like I am scraping the barrel a little here - my drawbacks are relatively inconsequential. But for the record they are:

Stop start

The two strand approach mentioned above, a narrative strand and a social history strand, never felt properly intertwined for me. When I was getting into the story I didn’t want a 20 minute hiatus on medieval haircuts, I just wanted to find out what happened next. So I ended up skipping the social history interludes and coming back to them at the end of the book, when I was able to take my time and better appreciate thirteenth century fashion tips.3

Why this charter?

The other thing to mention is that the book doesn’t try to explain why the Magna Carta has become so celebrated? How big a deal was it really? Is Magna Carta as medieval proto-liberalism myth-making or meaningful? Is a failed peace treaty attempting to make the king behave a bit better to a tiny privileged elite really significant? You can tell by the number of question marks in the paragraph that, after finishing Jones’ work, I don’t really have a clue. Although to be fair this topic would, and I’m certain already does, fill whole books by itself.

Deja Vu

The final discordant note is the fact that this book In the Reign of King John: A Year in the Life of Plantagenet England published in 2020 is a re-release of the same book Realm Divided: A Year in the Life of Plantagenet England published in 2015. I know that there can sometimes be good reasons to re-release a book with a different name, but most of the time I find it misleading and suspicious. Luckily I hadn’t already read Realm Divided when I bought this latest version.

Conclusion

But even though this book is of its time and place (i.e. the UK in 2015 to cash in on the anniversary of the Magna Carta) it still stands the test of time, being well worth a read seven years on.

It does a great job of convincing us that the Magna Carta, encapsulating that tumultuous year in England eight centuries ago, is a fun, exciting, and important document - still worth reading eight hundred years later.

Source: the internet ↩︎

A clause mandating the removal of all fish traps (”fish-weirs”) from all rivers in England is always mentioned as one of those “of-their-time” and esoteric clauses in the Magna Carta - I even remember this clause from my superficial review of the text way back in my university days. But I’ve never really understood why the fish traps were such a big deal. Jones has a throw-away line saying it was because they obstructed boats, and other twitterstorians have proposed it was because the traps were so darn good at catching fish that soon there would be no fish left. Neither of these suggestions feels definitive. So if you can put me in the direction of something more comprehensive on the subject drop me a line! ↩︎

Possibly my favourite bit of ye-olde colour was the belief, of at least one Medieval author, that “beavers would bite off their own testicles when pursued, since they knew that humans valued them for medicinal use.” Followed up by the statement that “Panthers breath was so sweet that it enticed every animal on earth to follow it - except for dragons, who detested the smell and would hide.” ↩︎

Book details

(back to top)- Title -

In the Reign of King John : A Year in the Life of Plantagenet England

- Author -

Dan Jones

- Publication date -

October 2020

- Publisher -

Apollo

- Pages -

400

- ISBN 13 -

978-1838934828

- Podcast episode -

- Podcast episode -

- Amazon UK -

- Amazon US -